- The Ammonite Shell

- The Web of Data 1: Threads and Futures

- The Web of Data 2 - Actors and Streams

- Appendix

This wiki page explains the why and how of banana-rdf in a practical way. This will help you getting started, in an easy step by step fashion using the Ammonite command line, and start making this library real with practical and fun examples of the Semantic Web.

We will explain the major concepts along the way in a step by step fashion which you can follow easily on the new Ammonite command line for yourself. The aim is to quickly get you to understand Linked Data by exploring it on the web using the banana-rdf library, so that you can start writing your own shell scripts and move on to larger programs the full value of this framework starts becoming clear.

Ammonite is the revolutionary Scala based shell, a typesafe replacement of bash, that makes scripting fun, safe and efficient.

Whereas in a unix shell, processes communicate through the singly typed string interface of the unix pipe, in Ammonite they communicate using composable typed functions, that can use the vast array of libraries written for Java and Scala. In the Unix shell each process has to parse the result of the previous as a simple string, which is both very innefficient and introduces potential dangerous errors that can only be spotted at runtime.

The Java based environement brings full Unicode support, mulithreaded programming, and programmatic access to the web, all of which can be now used directly from the shell.

In particular it should prove to be a great tool to start exploring the semantic web, as if it were part of your file system, write some small initial scripts to try out ideas, and make it part of your scripting environment.

- Download Ammonite Shell as described on their documentation page. For the newly released Ammonite 1.0 (4 July 2017) it is as easy as running the following two lines from the command line

$ mkdir -p ~/.ammonite && curl -L -o ~/.ammonite/predef.sc https://git.io/vHaKQ

$ sudo curl -L -o /usr/local/bin/amm https://git.io/vQEhd && sudo chmod +x /usr/local/bin/amm && ammbut check the latest on their excellently documented web site - (and update this wiki if there is a change).

For Windows Users we have found that it works well with the latest versions of Windows 10 Subsystem for Linux that supports Ubuntu 16.04 as of the 4th July 2017. (Otherwise check out Ammonite issue 119)

- start Ammonite

$ amm- Import the banana-rdf libraries. To to this run the following at the

@command prompt, which will be specific to your environment. I have removed the@prompt from may of these examples to make copy and pasting easier. After each of these lines you will see a response from the command prompt.

import coursier.core.Authentication, coursier.MavenRepository

interp.repositories() ++= Seq(MavenRepository(

"http://bblfish.net/work/repo/snapshots/"

))

import $ivy.`org.w3::banana-sesame:0.8.4-SNAPSHOT`those last imports will download a lot of libraries the first time round. Here we are choosing to use the Sesame implementation of banana. You could use another one, such as Jena.

todo: in the near future we will genericise the code to allow you to choose which version you prefer to use in a couple of lines of code

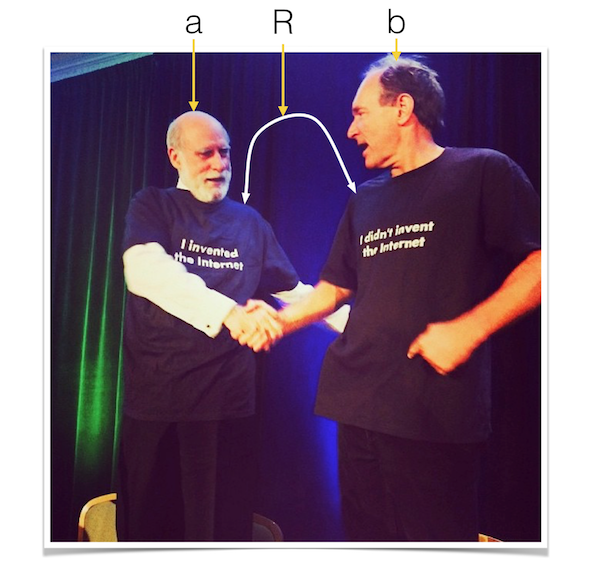

Next we are going to build an RDF graph. RDF, stands for Resoure Description Framework, and is used to describe things by relating them to one another. For

example we could describe the relation of Tim Berners Lee and Vint Cert as a relation aRb between them as shown in the picture below.

But if one were just given aRb without the picture, how could one know what it means? Where could one look up that information? How could one create new types of relations? This is what RDF - the Resource Description Framework - solves by naming relations and things with URIs, that can, especially if they are http or https URLs be dereferences from the web - as we will see in the next section - in order to glean more information from them.

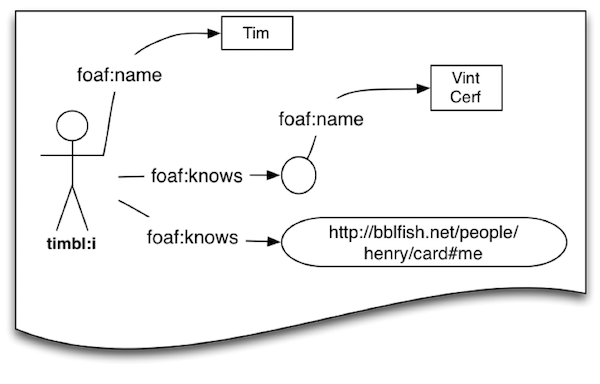

Here for example is a more detailed graph consisting of 4 arrows describing the relation between Tim, Vint Cert, and some other entity referred to by a long URL

<http://bblfish.net/people/henry/card#me>.

The relations are not written out in full in the above example, as that would be awkward to read and take up a lot of space. Instead we have relations named foaf:name and foaf:knows which are composed of two parts separated by a column: a namespace part 'foaf' which stands for http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/ followed by a string name or knows which can be concatenated together to form a URL, in this case http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/name and http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/name.

How do we write this out in banana-rdf?

First, we import the classes and functions we need. (I have removed the @ command line prompt to make it easier to copy and paste the whole lot in one go)

import org.w3.banana._

import org.w3.banana.syntax._

import org.w3.banana.sesame.Sesame

import Sesame._

import ops._Then we import the foaf ontology identifiers that

are predefined for us in the banana prefix file as they

are so useful. This makes a lot easier to read than having to write URIs out

completely. (here to show the interactive side I have left the @ prompt in, and the response

from running the code)

@ val foaf = FOAFPrefix[Sesame]

foaf: FOAFPrefix[Sesame] = Prefix(foaf)

@ val timbl: PointedGraph[Sesame] = (

URI("https://www.w3.org/People/Berners-Lee/card#i")

-- foaf.name ->- "Tim Berners-Lee".lang("en")

-- foaf.plan ->- "Make the Web Great Again"

-- foaf.knows ->- (bnode("vint") -- foaf.name ->- "Vint Cerf")

-- foaf.knows ->- URI("http://bblfish.net/people/henry/card#me")

)We can output that graph consisting of five relations (also known as "triples") in what is conceptually the simplest of all RDF formats: NTriples.

(Again here the output is important, so we kept the @ prompt. Only type the

that follows that prompt into your ammonite shell)

@ ntriplesWriter.asString(timbl.graph,"")

res54: Try[String] = Success(

"""<https://www.w3.org/People/Berners-Lee/card#i> <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/knows> <http://bblfish.net/people/henry/card#me> .

_:vint <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/name> "Vint Cerf"^^<http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema#string> .

<https://www.w3.org/People/Berners-Lee/card#i> <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/knows> _:vint .

<https://www.w3.org/People/Berners-Lee/card#i> <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/plan> "Make the Web Great Again"^^<http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema#string> .

<https://www.w3.org/People/Berners-Lee/card#i> <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/name> "Tim Berners-Lee"@en ."""

)The easiest format for humans to read and write RDF is the Turtle format, and you can see how the output here is somewhat similar to the Diesel banana-rdf DSL.

@ turtleWriter.asString(timbl.graph,"").getwhich will return the following Turtle:

<https://www.w3.org/People/Berners-Lee/card#i> <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/knows>

<http://bblfish.net/people/henry/card#me> , _:vint ;

<http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/plan> "Make the Web Great Again" ;

<http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/name> "Tim Berners-Lee"@en .

_:vint <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/name> "Vint Cerf" .And since nothing is cool nowadays if does not produce JSON, here is the JSON-LD rendition of it:

jsonldCompactedWriter.asString(timbl.graph,"").getwhich will return the following json

{

"@graph" : [ {

"@id" : "_:vint",

"http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/name" : "Vint Cerf"

}, {

"@id" : "https://www.w3.org/People/Berners-Lee/card#i",

"http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/knows" : [ {

"@id" : "http://bblfish.net/people/henry/card#me"

}, {

"@id" : "_:vint"

} ],

"http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/name" : {

"@language" : "en",

"@value" : "Tim Berners-Lee"

},

"http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/plan" : "Make the Web Great Again"

} ]

}For a full list of currently integrated serialisers look at the SesameModule.scala file.

(Note: It is very likely that there are newer json serialisers than the one that banana-rdf is using that produce much better output than this, as this has not been updated for over a year.)

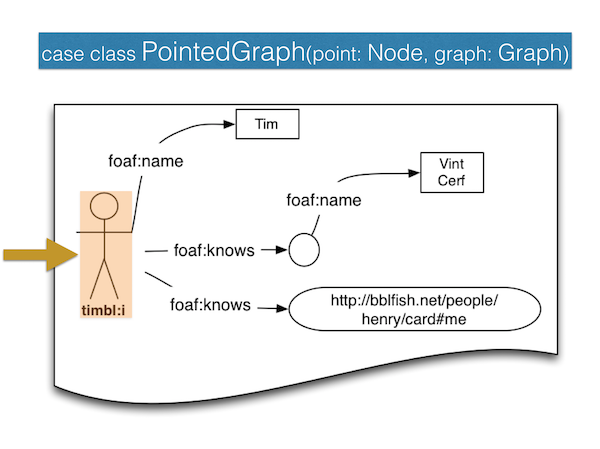

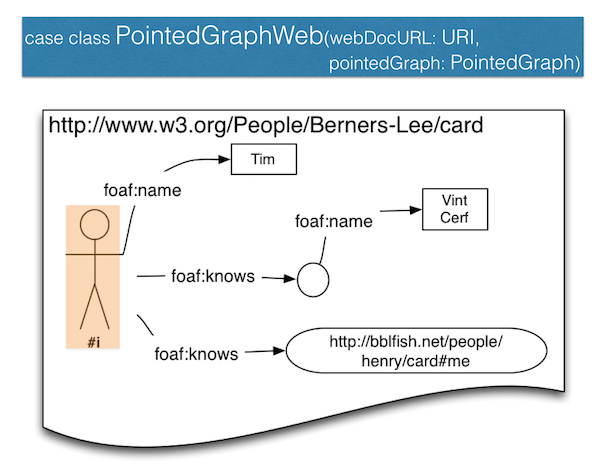

The attentive reader will have noticed that the Domain Specific Language (DSL) we used above to produce those outputs returned a PointedGraph. This is an extremely simple concept best illustrated by the following diagram, namely just the pair of a graph and a pointer into the graph.

So in our timbl graph, https://www.w3.org/People/Berners-Lee/card#i is the node pointed to.

This PointedGraph view allows us to move to an Object Oriented (OO) view of the graph. And indeed the PointedGraph type comes with some operations that are reminiscent of the OO dot . notation: the / for forward relation exploration and the /- for backward relation exploration.

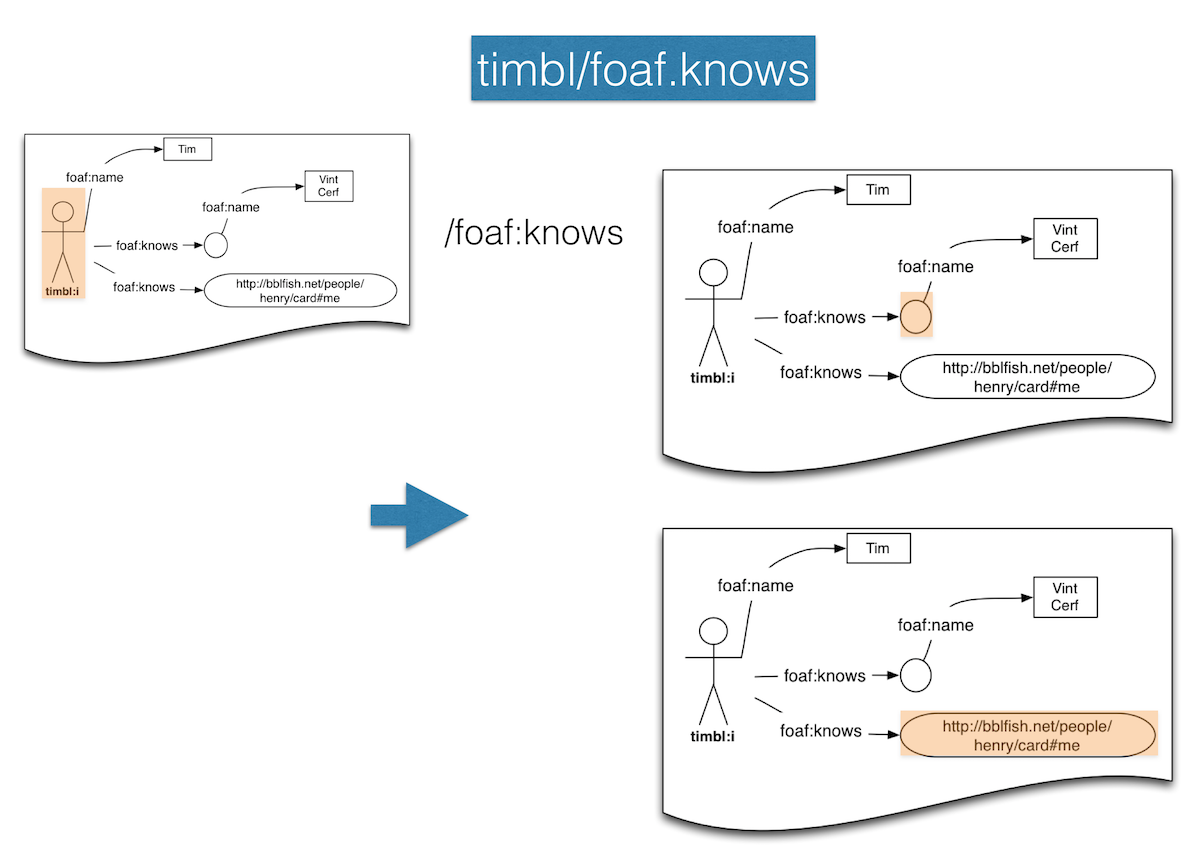

@ timbl/foaf.knows

res58: PointedGraphs[Sesame] = PointedGraphs(

org.w3.banana.PointedGraph$$anon$1@7d03b6aa,

org.w3.banana.PointedGraph$$anon$1@61f7c895

)Notice that if we don't give a name to a function return value Ammonite gives it a name. In this case res58, which we can use in the shell:

@ res58.map(_.pointer)

res59: Iterable[Sesame#Node] = List(http://bblfish.net/people/henry/card#me, _:vint)We can illustrate the above interaction with the following diagram. As you see the graph remains the same after each operation but the pointer moves.

Again this is very similar to OO programming when you follow an attribute to get its value.

You can explore more examples by looking at the test suite, starting from the diesel example.

Building our own graph and querying it is not very informative. So let's try getting some information from the world wide web.

First, let us load a simple Scala wrapper around the Java HTTP library, scalaj-http.

@ interp.load.ivy("org.scalaj" %% "scalaj-http" % "2.3.0")We can now start using banana-rdf on real data. One question of interest could be what this http://bblfish.net/people/henry/card#me url refers to in the graph above. So let's see what the web tells us.

@ import scalaj.http._

import scalaj.http._

@ val bblUrl = URI("http://bblfish.net/people/henry/card#me")

bblUrl: Sesame#URI = http://bblfish.net/people/henry/card#meThe HTTP RFC does not allow one to make requests with fragment identifiers, since the URI RFC defines fragment identifiers as

The fragment identifier component of a URI allows indirect identification of a secondary resource by reference to a primary resource and additional identifying information. The identified secondary resource may be some portion or subset of the primary resource, some view on representations of the primary resource, or some other resource defined or described by those representations. A fragment identifier component is indicated by the presence of a number sign ("#") character and terminated by the end of the URI.

In our language URIs with fragment identifiers refer to pointed graphs. So we remove the fragment before making the HTTP request.

@ bblUrl.fragmentLess

res63: Sesame#URI = http://bblfish.net/people/henry/card

@ val bblReq = Http( bblUrl.fragmentLess.toString )

bblReq: HttpRequest = HttpRequest(

"http://bblfish.net/people/henry/card",

"GET",

DefaultConnectFunc,

List(),

List(("User-Agent", "scalaj-http/1.0")),

List(

scalaj.http.HttpOptions$$$Lambda$111/614609966@15edb703,

scalaj.http.HttpOptions$$$Lambda$113/286344087@5dbab6b0,

scalaj.http.HttpOptions$$$Lambda$114/1231971264@4747e542

),

None,

"UTF-8",

4096,

QueryStringUrlFunc,

true

)That sets the request. The ammonite shell shows us the structure of the

request, consisting of a number of headers, including one which sets

the name of the User-Agent to "scalaj-http".

Next, we make the request and retrieve the value as a string. If your internet connection is functioning and the bblfish.net server is up, you should get something like the following result.

@ val bblDoc = bblReq.asString

bblDoc: HttpResponse[String] = HttpResponse(

"""@prefix rdf: <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#> .

@prefix : <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/> .

@prefix cert: <http://www.w3.org/ns/auth/cert#> .

@prefix contact: <http://www.w3.org/2000/10/swap/pim/contact#> .

@prefix iana: <http://www.iana.org/assignments/relation/> .

@prefix owl: <http://www.w3.org/2002/07/owl#> .

@prefix pingback: <http://purl.org/net/pingback/> .

@prefix rdfs: <http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#> .

@prefix space: <http://www.w3.org/ns/pim/space#> .

<http://axel.deri.ie/~axepol/foaf.rdf#me>

a :Person ;

:name "Axel Polleres" .

<http://b4mad.net/FOAF/goern.rdf#goern>

a :Person ;

..."""

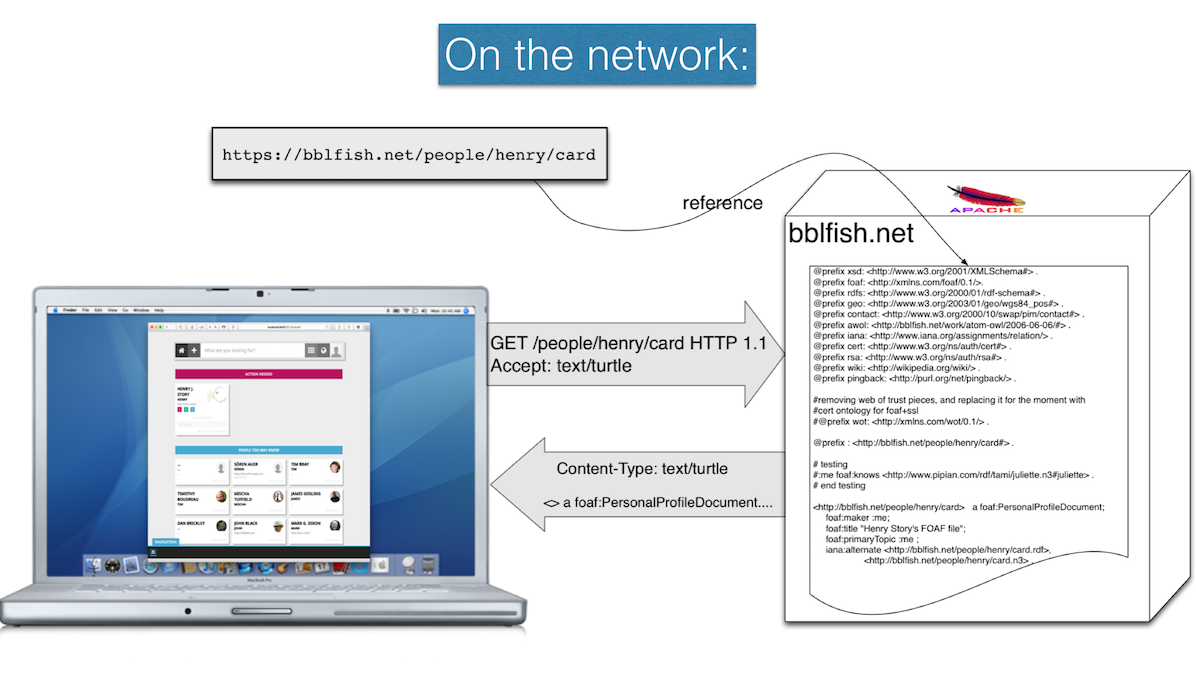

This following illustration captures the interaction between your computer and the bblfish.net server when you make this request.

This illustrates the request made from JavaScript in the browser, which then displays that data using a Scala-JS program available in the rww-scala-js repository.

But before we go on writing user interfaces for people who will never know what RDF is, requiring us to work with Web Designers, artists, psychologists and others, let us stick to the command line interface. We need to learn how this works so that we can then build tools for people who don't.

So having downloaded the Turtle, we just need to parse it into a graph and

point onto a node of the graph (a PointedGraph) to explore it. (The turtle parser is inherited by the ops we imported earlier defined in the SesameModule)

@ val bg = turtleReader.read(new java.io.StringReader(bblDoc.body), bblUrl.fragmentLess.toString)

bg: Try[Sesame#Graph] = Success(

[(http://axel.deri.ie/~axepol/foaf.rdf#me, http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type, http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/Person) [null], (http://axel.deri.ie/~axepol/foaf.rdf#me, http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/name, "Axel Polleres"^^<http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema#string>) [null], ...])Having the graph we construct the pointed graph, allowing us then to explore it as we did in the previous section. But here we are likely to learn something new, since we did not put this data together ourselves.

@ val pg = PointedGraph[Sesame](bblUrl,bg.get)

pg: PointedGraph[Sesame] = org.w3.banana.PointedGraph$$anon$1@353b86bc

@ (pg/foaf.name).map(_.pointer)

res72: Iterable[Sesame#Node] = List("Henry J. Story"^^<http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema#string>)So now we know the name of the person with the bblfish url. We can see who he claims to know with the following query.

@ val knows = pg/foaf.knows

knows: PointedGraphs[Sesame] = PointedGraphs(

org.w3.banana.PointedGraph$$anon$1@53dc5333,

org.w3.banana.PointedGraph$$anon$1@787fdb85,

...)And we can find out how many they are, what their names are, and much more.

@ knows.size

res71: Int = 74

@ (knows/foaf.name).map(_.pointer)

res45: Iterable[Sesame#Node] = List(

"Axel Polleres"^^<http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema#string>,

"Christoph Görn"^^<http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema#string>,

...)Above we have explored the data in one remote resource. But what about the documents that resource links to?

In the Friend of a Friend profile we downloaded above, Henry keeps the names of the people he knows, so that

- if a link goes bad, he can remember whom he intended the link to refer to (in order to fix it if possible)

- to allow user interfaces to immediately give some information about what he was intending to link to, without having to downloading more information.

But most of the information is actually not in his profile - why after all should he keep his profile up to date about where his friends live, who their friends are, what their telephone number is, where their blogs are located, etc...? If he did not share responsibility with others in keeping data up to date, he would soon have to maintain all the information in the world.

That is where linked data comes in: it allows different people and organisations to share the burden of maintaining information. The URLs used in the names of the relations and the names of the subjects and objects refer (directly and often indirectly via urls ending in #entities) to documents maintained by others - in this case the people Henry knows.

So the next step is to follow links from one resource to another, download those documents, turn them

into graphs, etc... We can do this if the pointers of the PointedGraph we named knows

are urls that don't belong to the original document (ie are not #urls that belong to that document,

blank nodes or literals). Then for each such URL url having downloaded the documents that those URLs point to, parsed them into a graph g and created a pointed graph PointedGraph(url,g) we can then continue

exploring the data from that location.

We need to automate this process as much as possible though. In the above example we asked for the default representation of the henryDocUrl resource.

As it happened it returned Turtle, and we were then able to use the right parser. But we would like a library to automate this task so that the software can follow the knows/foaf.knows links to other pages automatically.

Let us write this then as little scripts and see how far we get.

So, first of all, we'd like to have one simple function that takes a URL and returns the pointed graph of that URL if successful or some explanation of what went wrong.

A little bit of playing around and we arrive at this function, that nicely gives us all the information we need:

@ def fetch(point: Sesame#URI): HttpResponse[scala.util.Try[PointedGraph[Sesame]]] = {

val docUrl = point.fragmentLess.toString

Http(docUrl).execute{ is =>

turtleReader.read(is,point.fragmentLess.toString)

.map{ g => PointedGraph[Sesame](point,g) }

}

}

defined function fetchIt keeps all the headers that we received, which may be useful for the extra information they contain, it gives us the content transformed into a pointed graph or an error in case of parsing errors.

But it is not quite right. There are two problems both related to the various syntaxes that RDF can be published in:

-

As we follow links on the web we would like to tell the server we come across what types of mime types we understand so we increase the likelihood that it sends one we can parse. For Sesame we currently can parse the following syntaxes for RDF: RDF/XML popular in the early 2000s when XML was popular, NTriples the easiest to parse, Turtle the easiest to read, json-ld popular because of it's encoding in JSON.

-

When we receive the response we need to select the parser given the mime type of the document returned by the server.

Here is a version that addresses both of these questions:

import scala.util.{Try,Success,Failure}

case class IOException(docURL: Sesame#URI, e: java.lang.Throwable ) extends java.lang.Exception

def fetch(docUrl: Sesame#URI): Try[HttpResponse[scala.util.Try[Sesame#Graph]]] = {

assert (docUrl == docUrl.fragmentLess)

Try( //we want to catch connection exceptions

Http(docUrl.toString)

.header("Accept", "application/rdf+xml,text/turtle,application/ld+json,text/n3;q=0.2")

.exec { case (code, headers, is) =>

headers.get("Content-Type")

.flatMap(_.headOption)

.fold[Try[(io.RDFReader[Sesame, Try, _],String)]](

Failure(new java.lang.Exception("Missing Content Type"))

) { ct =>

val ctype = ct.split(';')

val parser = ctype(0).trim match {

case "text/turtle" => Success(turtleReader)

case "application/rdf+xml" => Success(rdfXMLReader)

case "application/n-triples" => Success(ntriplesReader)

case "application/ld+json" => Success(jsonldReader)

case ct => Failure(new java.lang.Exception("Missing parser for "+ct))

}

parser.map{ p =>

val attributes = ctype.toList.tail.flatMap(

_.split(',').map(_.split('=').toList.map(_.trim))

).map(avl => (avl.head, avl.tail.headOption.getOrElse(""))).toMap

val encoding = attributes.get("encoding").getOrElse("utf-8")

(p, encoding)

}

} flatMap { case (parser,encoding) =>

parser.read(new java.io.InputStreamReader(is, encoding), docUrl.toString)

}

}).recoverWith{case t => Failure(IOException(docUrl,t))}

}The above functions show that dealing with the mime types is a little tricky perhaps, but not that difficult. The code was written entirely in the Ammonite shell (and that is perhaps the longest piece of code that makes sense to write there).

@ val bblgrph = fetch(bblUrl.fragmentLess)

bblgrph: Try[HttpResponse[Try[org.openrdf.model.Model]]] = Success(

HttpResponse(

Success(

[(http://axel.deri.ie/~axepol/foaf.rdf#me, http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type, http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/Person) [null], (http://axel.deri.ie/~axepol/foaf.rdf#me, http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/name, "Axel Polleres"^^<http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema#string>) [null],...]))Note that we have wrapped the response in a Try to catch any connection errors that might occur when we make the HTTP connection. We then wrap any error in our IOException where we place the URL of the page that was requested so that we can later trace those errors back to the URL that caused them.

We may be interested to know how many friends bblfish has written up in his profile. For that we need to first get a PointedGraph. (I have specified the types of each object returned below in order to make reading easier.)

val bblfish: PointedGraph[Sesame] = PointedGraph[Sesame](bblUrl,bblgrph.get.body.get)

val bblFriends: PointedGraphs[Sesame] = bblfish/foaf.knows

val friendIds: Iterable[Sesame#Node] = bblFriends.map(_.pointer)As an interesting side note, Ammonite provides some interesting short

hand to make the parallel between programming with functions and (programming with pipes in the unix shell)[http://linuxcommand.org/lts0060.php] more apparent. One can

think of a the above map function as taking the output of one process, and

piping it into the (x: PointedGraph[Rdf]) => x.pointer function. So that one can rewrite the last two lines as

val friendIds = bblfish/foaf.knows | ( _.pointer )We'll get back to more of that later.

Once we have these ids, we can then find out a few things from it, such as what types of nodes we have there.

@ friendIds.size

res52: Int = 74

@ val nodeTypes = friendIds.groupBy{ (u: Sesame#Node) => nodeW(u).fold[String](uri =>"uri", bnode=>"bnode", lit=>"literal") }

res50: Map[String, Iterable[Sesame#Node]] = Map(

"uri" -> List(

http://axel.deri.ie/~axepol/foaf.rdf#me

...)) The nodeTypes is quite a large data structure, so it is easier

to browse it with browse(nodeTypes) in Ammonite: this will open a viewer

so that you can step through the pages without clogging up your

shell history.

We can also query that data structure programmatically like this:

@ nodeTypes("uri").size

res55: Int = 60

hjs-banana-rdf.wiki@ nodeTypes("bnode").size

res56: Int = 14

So there are 14 people listed as being known by bblfish that are refered to by a blank node, that is without a direct WebID to allow a client to easily jump to more information. We can think of those nodes as requiring a description to allow us to identify who is being spoken of. All we have is the information in that graph.

But we may have missed out on something. The [foaf ontology](http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/] also alows people to express memberships of groups. How many groups does bblfish belong to? Let us see...

@ val groupIds = bblfish/-foaf.member | ( _.pointer )

groupIds: Iterable[Sesame#Node] = List()

@ (bblfish/foaf.holdsAccount | ( _.pointer )).size

res88: Int = 10In the first request we are looking if there is a foaf.member from a group to bblfish in that document (none it seems). And in the second we are looking how many accounts bblfish holds (10). So this gives an overview of exploring

a graph just by following links inside the graph.

As we will want to fetch a number of graphs by following the foaf:knows links, we would like to do this in parallel.

At this point, the java.net.HttpURLConnection starts showing its age and limitations as it is a blocking call that holds onto a thread. And threads are expensive: over half a MB each. This may not sound like a lot but if you want to open 1000 threads simultaneously you would end up using up half a Gigabyte just in thread overhead, and your system would become very slow as the Virtual Machine will keep jumping through 1000 threads just waiting to see if any one of them has something to parse, where most of the time they won't - as internet connections are close to 1 billion times slower than fetching information from an internal CPU cache.

But in order to avoid bringing in too many other concepts at this point let us deal with this the simple way, using threads and Futures. This will be good enough for a demo application and will provide a stepping stone to the more advanced tools. It will also make sure that you will notice if you start hammering the internet, as your computer will slow down quite quickly.

So, first of all, we need an execution context. We don't want to use the scala.concurrent.ExecutionContext.global

default one, as we may easily create a lot of threads. So we create our own. (Remember we can later take this code and turn it into a script that we can import in one go.)

import scala.concurrent.{Future,ExecutionContext}

import java.util.concurrent.ThreadPoolExecutor

val threadPooleExec = new ThreadPoolExecutor(2,50,20,java.util.concurrent.TimeUnit.SECONDS,new java.util.concurrent.LinkedBlockingQueue[Runnable])

implicit lazy val webcontext = ExecutionContext.fromExecutor(threadPooleExec,err=>System.out.println("web error: "+err))Next, we can create a very simple cache class. This one is not synchronised and should only be used by one thread.

It would be easy to create a more battle proof cache with java.util.concurrent.atomic.AtomicReference, but I'll leave that as an exercise to the reader. This makes the code easier to read.

case class HttpException(docURL: Sesame#URI, code: Int, headers: Map[String, IndexedSeq[String]]) extends java.lang.Exception

case class ParseException(docURL: Sesame#URI, parseException: java.lang.Throwable) extends java.lang.Exception

class Cache(implicit val ex: ExecutionContext) {

import scala.collection.mutable.Map

val db = Map[Sesame#URI, Future[HttpResponse[Try[Sesame#Graph]]]]()

def get(uri: Sesame#URI): Future[HttpResponse[Try[Sesame#Graph]]] = {

val doc = uri.fragmentLess

db.get(doc) match {

case Some(f) => f

case None => {

val res = Future.fromTry( fetch(doc) )

db.put( doc, res )

res

}

}

}

def getPointed(uri: Sesame#URI): Future[PointedGraphWeb] =

get(uri).flatMap{ response =>

if (! response.is2xx ) Future.failed(HttpException(uri, response.code, response.headers))

else {

val moreTryInfo = response.body.recoverWith{ case t => Failure(ParseException(uri,t)) }

Future.fromTry(moreTryInfo).map{g=>

PointedGraphWeb(uri.fragmentLess,PointedGraph[Sesame](uri,g),response.headers.toMap)

}

}

}

case class PointedGraphWeb(webDocURL: Sesame#URI,

pointedGraph: PointedGraph[Sesame],

headers: scala.collection.immutable.Map[String,IndexedSeq[String]]) {

def jump(rel: Sesame#URI): Seq[Future[PointedGraphWeb]] =

(pointedGraph/rel).toSeq.map{ pg =>

if (pg.pointer.isURI) Cache.this.getPointed(pg.pointer.asInstanceOf[Sesame#URI])

else Future.successful(this.copy(pointedGraph=PointedGraph[Sesame](pg.pointer, pointedGraph.graph)))

}

}

}Because dealing with types such as Future[HttpResponse[Try[Sesame#Graph]]] returned by the Cache.get

method, it is easier to compress that information into a PointedGraphWeb, which is a pointedGraph on the web. It contains the name of the graph, and some headers so that one can also work out the version and date of it.

Here is a slightly simplified picture of a PointedGraphWeb in the style of the previous ones:

@ val cache = new Cache()

cache: Cache = ammonite.$sess.cmd162$Cache@64454830

@ val bblFuture = cache.getPointed(URI("http://bblfish.net/people/henry/card#me"))

res164: Future[HttpResponse[Try[org.openrdf.model.Model]]] = Future(<not completed>)At this point, the bblFuture a Future of an HttpResponse is <not completed>. But if we wait just a little we get:

@ bblFuture.isCompleted

res165: Boolean = trueGood! so we can use the above now to follow the links. First let's unwrap the future to get at its PointedGraphWeb content, which means digging through a few layers of this layer monad.

@ val pgw = bblFuture.value.get.get

pwg: cache.PointedGraphWeb = PointedGraphWeb(

http://bblfish.net/people/henry/card,

org.w3.banana.PointedGraph$$anon$1@34245b5d,

Map(...))Though we may do this from time to time on the command line, we don't really want our programs to block waiting for a future to be finished.

Then we can use the jump to get all the other foaf files linked

to from bblfish's profile.

@ val bblFoafs = pgw.jump(foaf.knows)

res27: Seq[Future[cache.PointedGraphWeb]] = Stream(

Future(<not completed>),

Future(<not completed>),

Future(<not completed>),

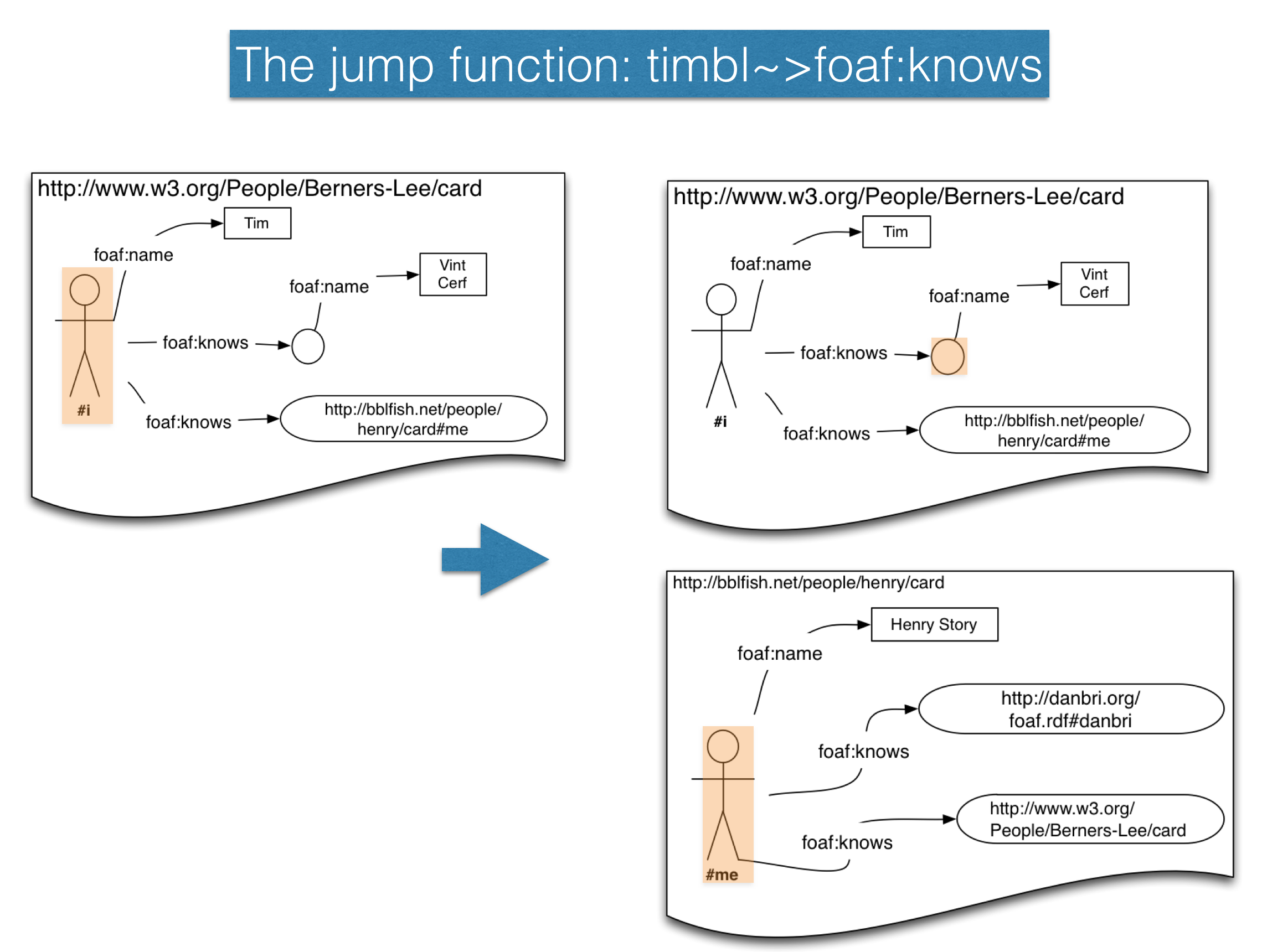

...)Here is a picture that shows how the jump function (also written ~>)

differs from the / function we used previously.

Notice that in the first result returned in the image the name of the graph and the graph are still the same. This is because Vint Cerf's is represented by a blank node, and not a URL so there is no place to jump. On the other hand the bblfish.net url, there is a place to jump. And that is indeed where we did jump: it is the graph that we have been looking at since the last section. But the result of our programmatically run jump across all of the other links comes to over 70 new links.

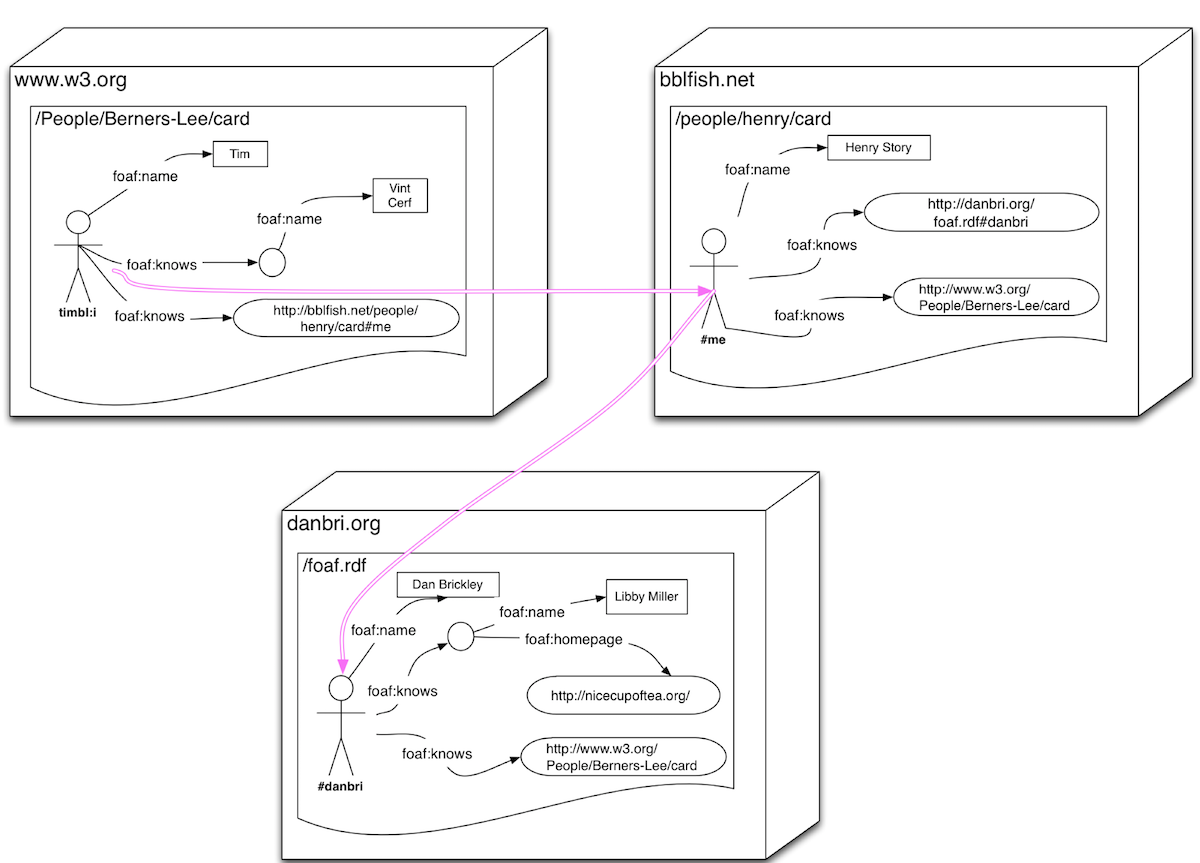

The previous diagram does not show the servers that are jumped across. As this is very important to understanding the difference between what the semantic web allows and normal siloed data strategies make possible, I have added this to the picture below. Note that we did not jump across just 2 servers, but tried to access something close to

70 different servers in our above jump call!

If a little later we try again we will see that more and more of the futures are completed, we can the start looking at the results to see what the problems with the links may be:

@ val finished = bblFoafs.map(_.value).filter(! _.isEmpty).toList.size

finished: Int = 74

@ val successful = bblFoafs.map(_.value).filter(optRes => !optRes.isEmpty && optRes.get.isSuccess)

successful: Seq[Option[Try[cache.PointedGraphWeb]]] = Stream(

Some(

Success(

PointedGraphWeb(

http://crschmidt.net/foaf.rdf,

org.w3.banana.PointedGraph$$anon$1@6fd7afad,

...)))

@val failure = bblFoafs.map(_.value).filter(optRes => !optRes.isEmpty && optRes.get.isFailure)

failure: Seq[Option[Try[cache.PointedGraphWeb]]] = Stream(

Some(

Failure(

HttpException(

http://axel.deri.ie/~axepol/foaf.rdf#me,

302,...))))

@ successful.size

res38: Int = 25

@ failure.size

res39: Int = 49So it looks like we have quite a lot of failures. That may well be. Henry has not had a tool to verify his foaf profile before, so he has not been able to keep his profile fresh.

With these tools we can see that we are well on our way to making this much easier, and well on our way to start automating it...

Conscientious friends are friends who link back to one. This has not been easy until now as there have been no good UIs to automate this or to remind one to update ones profile. The aim of this document is to make it easy for people to automate all these processes, including the notification of broken links to help maintain the linked data web in good form.

So to do this we need to

- jump on the foaf.knows relation for the WebID we are interested in

- for each of the remotely jumped to graphs select those nodes that have a

foaf.knowsrelation back to the initial WebId.

Scala's type system comes in very helpful when writing code like this. Here is the answer we came up with:

def sequenceNoFail[A](seq :Seq[Future[A]]): Future[Seq[Try[A]]] =

Future.sequence{ seq.map(_.transform(Success(_)))}

def conscientiousFriend(webID: Sesame#URI)(implicit cache: Cache): Future[Seq[(Sesame#URI, Option[PointedGraph[Sesame]])]] = {

for{

friendsFuture: Seq[Future[cache.PointedGraphWeb]] <- cache.getPointed(webID).map(_.jump(foaf.knows)) //[1]

triedFriends: Seq[Try[cache.PointedGraphWeb]] <- sequenceNoFail(friendsFuture) //[2]

)

} yield {

triedFriends.collect { [3]

case Success(cache.PointedGraphWeb(doc,pg,_)) =>

val evidence = (pg/foaf.knows).filter((friend: PointedGraph[Sesame]) => webID == friend.pointer && friend.pointer.isUri)

(doc, evidence.headOption)

}

}

}In the line marked [1] we jump to each remote foaf.knows. In line [2] we transform the Seq of Futures into a Future[Try[Seq]] which will always succeed ( we don't want our function to fail because one server is down ). Finally in the block [3] we filter out only the succesful requests, and see if the that pointed graph has the desired foaf.knows relation to the original WebID. We return the URL found as evidence so that the caller knows where to look, if at all.

It is intersting to look at what this looks like if one takes the Unix Pipes analogy of functions seriously.

import $exec.FutureWrapper

cache.getPointed(webId) | (_.jump(foaf.knows)) || sequenceNoFail | (_ |?| {

case Success(cache.PointedGraphWeb(doc,pg,_)) =>

val evidence = (pg/foaf.knows).filter((friend: PointedGraph[Sesame]) => webId == friend.pointer && friend.pointer.isUri)

(doc, evidence.headOption)

})So here we can think of cache.getPointed(webId) as returning a Future PointedGraphWeb. This PointedWebGraph web is streamed using | (in the future) to the jump function, which outputs a Seq[Future[PointedGraphWeb]]. This is the passed (in the future) via '||' (ie. flatMap) to the sequenceNoFail method, which transforms that output into a new Future of Sequences which replaces the previous ones, placing us now at the outer edge of the future, as all the previous futures have to be finished before the results of that outer future can be collected with |?|.

We may want to improve this by following rdfs:seeAlso links or links to foaf:Groups as those may be where the return links have been placed. Actually, I urge the reader to try that and find out how difficult this Future based monadic programing starts becomeing.

This document is about introducing people to banana-rdf with an example that makes it clear why this framework is useful. with data that spans organisations, just as html hypertext only makes sense if one publishes one's documents in a global space (otherwise word documents would have been fine). This required going beyond what banana-rdf offers, by tying it into http requests etc... There is a lot more to be said about that.

Still, this little experiment has shown quite a few things that would need to be produced by a good web cache library:

- it would need to limit requests to servers in an intelligent way in order to avoid flooding a server and getting the user banned from connecting. There are well-known rules for how crawlers should behave, and the code using the cache is getting close to being a crawler

- it would be good if that web cache used as few threads as possible (eg. by using an actor framework, such as akka or akka-http)

- the web cache should save the downloaded files to the local disk so that restart does not require fetching nonexpired files again

It would be nice to enhance the demonstration with the code the rest of the solid feature lists such as:

- Authentication with WebID

- Access Control

- Read-Write features given by LDP

IT may be that those make more sense in a different project, as they go too far from being directly relevant to banana-rdf. When such libraries do come to appear, it would be good if those projects continued the work here to show how to quickly get going with those libraries using Ammonite.

In order to be able to test new ideas more quickly without having to copy and paste from this wiki page all the time, the code has been placed in a script on this page at ammonite/Jump.sc.

You can just download it locally to execute it, or even clone the git wiki repository as mentioned on the root of this wiki.

So in the previous section we covered all the basics of what we can understand to be an extension of the hypertext based web into hyper data. But we saw that if we use the traditional thread based programming method, that has the advantage of at least locally making it look to a user that he is programming sequentially, the cost mounts very quickly as each thread takes up half a MB of memory just by itself. The Future based programming that wraps that has the advantage of hiding the complexity of synchronisation, but requires one to work as if there was no time - one has to wait for the whole computation to finish before retrieving an answer. If we try to use callbacks on futures to get answers as they arrive then we need to process these results as a stream. Stream based computation is co-algebraic, and this brings a whole new dimension to programming which is required if we want to be able to efficiently explore the web of data.

Akka is a Scala Actor library that makes it possible to increase by potentially a factor of a million the effectiveness of threads, especially when working with IO over the internet, as the speed at which information comes back over the internet can be a factor of a billion times slower than the fastest calculation on the cpu.

Actors are named entities that have an inbox of messages that they can look into and process and when done potentially send a message to another actor. A scheduler can by taking into account inbox size or other features prioritizes which actor will run next - and potentially on which thread they should run on. This maps very nicely to TCP/IP and internet communication which is message based.

Actors are 1000 times less hungry in memory than threads are. Where 2000 threads would take a GigaByte of heap space, one can get close to 2.5 million actors in that same space. But they are also much more effective at using the cpu, because actors usually always have something to do when they are called, whereas that may not at all be the case for threads waiting on IO.

Because Actors are such a good model for IO, Akka comes with a Streams library built on those actors and an HTTP library built on that Stream model (for more detail see the docs)

But there are many other nice features that come out of the box with Akka, and that are worth mentioning:

- The Akka Http client library makes sure that requests to web servers are limited so as not to overload a host and risk being banned from the hosts operator. See the explanation for Pool overflow and the max-open-requests setting. It is worth looking at the akka-http-core Reference Config File to see what other parameters can be tuned.

- Akka Http headers are strongly typed, making it possible for the compiler to detect mistakenly formed headers

- It comes with a serialisation/deserialisation library, making it possible to plug various serialisers together functionally.

In this section we will show how to build some simple hyper data based applications based on streams and banana-rdf in order to overcome the previous limitations we discovered with threads and Futures. We will do this by going over important parts of the Ammonite Script akkaHttp.sc that has been placed in this wiki. But unlike the previous section we won't go over every step in full detail.

Importing Akka HTTP and its dependency is a simple as pasting this one line into the ammonite shell.

import $ivy.`com.typesafe.akka::akka-http:10.0.9`The main libraries we need are then important for use in the shell/script with

import akka.actor.ActorSystem

import akka.actor.SupervisorStrategy

import akka.http.scaladsl.Http

import akka.http.scaladsl.model.{Uri=>AkkaUri,_}

import akka.stream.{ActorMaterializer, ActorMaterializerSettings,Supervision,_}

import akka.stream.scaladsl._

import akka.{ NotUsed, Done }

import akka.event.LoggingWe then just need to start the Actor environement with

val shortScriptConf = ConfigFactory.parseString("""

|akka {

| loggers = ["akka.event.Logging$DefaultLogger"]

| logging-filter = "akka.event.DefaultLoggingFilter"

| loglevel = "ERROR"

|}

""".stripMargin)

implicit val system = ActorSystem("akka_ammonite_script",shortScriptConf)

val log = Logging(system.eventStream, "banana-rdf")

implicit val materializer = ActorMaterializer(

ActorMaterializerSettings(system).withSupervisionStrategy(Supervision.resumingDecider))

implicit val ec: ExecutionContext = system.dispatcherThis time we will not mention the Sesame implementation of banana-rdf

explicity when using each types, as we did in the previous section

instead we will just use the Rdf value imported by Sesame which

identifies that with Sesame. If we switch to the well known Java Jena

library, or our banana's own Plantain library, those will import an

identically named Rdf value but this time tied to the different implementation.

As a result the only thing we will need to change are the

few imports where those names appear:

import $ivy.`org.w3::banana-sesame:0.8.4-SNAPSHOT`

import org.w3.banana.sesame.Sesame

import Sesame._

import Sesame.ops._Todo: give the above imports for Jena and Plantain

Akka's whole HTTP layer is strongly typed, allowing errors in constructing

HTTP headers or in parsing them to be caught at compilation time. And indeed

even mime types are strongly typed objects. Akka does not come with the RDF

mime types, so we just build them ourselves in the RdfMediaTypes object.

val `text/turtle` = text("turtle","ttl")

val `application/rdf+xml` = applicationWithOpenCharset("rdf+xml","rdf")

val `application/ntriples` = applicationWithFixedCharset("ntriples",`UTF-8`,"nt")

val `application/ld+json` = applicationWithOpenCharset("ld+json","jsonld")For RDFa we can just use the Akka provided default HTML mime type.

We can then create our Unmarshallers for the 4 most used rdf mime types, which

will be used to transform the stream of an HTTP connection to an Rdf#Graph.

def rdfUnmarshaller(requestUri: AkkaUri): FromEntityUnmarshaller[Try[Rdf#Graph]] = {

import Unmarshaller._

//todo: use non blocking parsers

val rdfunmarshaller = PredefinedFromEntityUnmarshallers.stringUnmarshaller mapWithInput { (entity, string) ⇒

val reader = entity.contentType.mediaType match { //<- this needs to be tuned!

case `text/turtle` => turtleReader

case `application/rdf+xml` => rdfXMLReader

case `application/ntriples` => ntriplesReader

case `application/ld+json` => jsonldReader

}

reader.read(new java.io.StringReader(string),requestUri.toString)

}

rdfunmarshaller.forContentTypes(`text/turtle`,`application/rdf+xml`,`application/ntriples`,`application/ld+json`)

}Todo: add RDFa unmarshaller

Notice that because banana-rdf does not have a non-blocking parser API, we need to read the whole string into memory and then parse it. Non blocking streaming parsers could be very useful in many scenarios such as when the aim is just to save the data to a database, or in the case where the need is just to pass it along. See issue 211 on that topic. But even here it is clear that it could save having to store the original stream in memory, and just construct the graph.

Todo: show how the mime types are strongly typed

To get started we can use Akka's Future based method for fetching a

resource on the web Http().singleRequest(req). We can incorporate

a future into a stream so this won't be a problem. Later when our demos

work for code we understand we can write a Stream based request service.

First we have a method to build an RDF focused HttpRequest object

for fetching a particular Uri.

def rdfRequest(uri: AkkaUri): HttpRequest = {

import RdfMediaTypes._

import akka.http.scaladsl.model.headers.Accept

HttpRequest(uri=uri.fragmentLess)

.addHeader(Accept(`text/turtle`,`application/rdf+xml`,

`application/ntriples`,`application/ld+json`))

}Here we could set preferences for each mime type depending on what the estimated quality of our parsers are. It would clearly help to add an RDFa parsers there too, though this would require a request on html mime type, which is most often less likely to contain any RDF at all, and so should have slightly less priority than the pure RDF mime types.

Next we can use that to build a simple RDF GET request:

def GET(uri: AkkaUri, maxRedirect: Int=4): Future[HttpResponse] = httpRequire(rdfRequest(uri),maxRedirect)since Akkas Http layer does not deal directly with redirects we can

repurpose a piece of code found on the akka github repository to provide this.

This is useful, as this part is often wrongly implemented.

Todo: Check that this implementation is correct as far as redirects go

//see: https://github.com/akka/akka-http/issues/195

def httpRequire(req: HttpRequest, maxRedirect: Int = 4)(implicit

system: ActorSystem, mat: Materializer): Future[HttpResponse] = {

try { //<- is this try still needed? if it is report to issue 1276

import StatusCodes._

Http().singleRequest(req)

.recoverWith{case e=>Future.failed(ConnectionException(req.uri.toString,e))}

.flatMap { resp =>

resp.status match {

case Found | SeeOther | TemporaryRedirect | PermanentRedirect => {

log.info(s"received a ${resp.status} for ${req.uri}")

resp.header[headers.Location].map { loc =>

val newReq = req.copy(uri = loc.uri)

if (maxRedirect > 0) httpRequire(newReq, maxRedirect - 1) else Http().singleRequest(newReq)

}.getOrElse(Future.failed(HTTPException(req.uri.toString,s"Location header not found on ${resp.status} for ${req.uri}")))

}

case _ => Future.successful(resp)

}

}

} catch {

case NonFatal(e) => Future.failed(ConnectionException(req.uri.toString,e))

}

}(Care must be taken to catch exceptions. Sadly Scala does not provide compiler support for finding those see issue 1276.)

Next we need to parse the content returned into an RDF Graph when possible. This

is done by the GETrdf function.

def GETrdf(uri: AkkaUri): Future[IRepresentation[Rdf#Graph]]This returns Futures of IRepresentation[Rdf#Graph] type objects. The IRepresentation type allows us to keep as much information about the Resonse object, such as headers and status code as we may need these later for a Cache object for example, to determine if the representation is stale and if therefore a new representation needs to be fetched from the origin resource). This data structure is more flexible that the Akka representation in that it allows us to begin interpreting the content into more advanced structures such as in the case above, into an Rdf#Graph. So we move from a pure binary representation of a resource to an interpreted one.

case class IRepresentation[C](origin: AkkaUri, status: StatusCode, headers: Seq[HttpHeader], content: C) {

def map[D](f: C => D) = this.copy(content=f(content))

}We can then provide a map function to allow us to map between types of content,

so we can then easily define functions from a Rdf#Graph to PointedGraph[Rdf]

in one line.

def pointedGET(uri: AkkaUri): Future[HttpRes[PointedGraph[Rdf]]] =

GETrdf(uri).map(_.map(PointedGraph[Rdf](uri.toRdf,_)))So as a quick reminder on what we want to do from our work in the previous section in The Web of Data 1: we wish to be able to

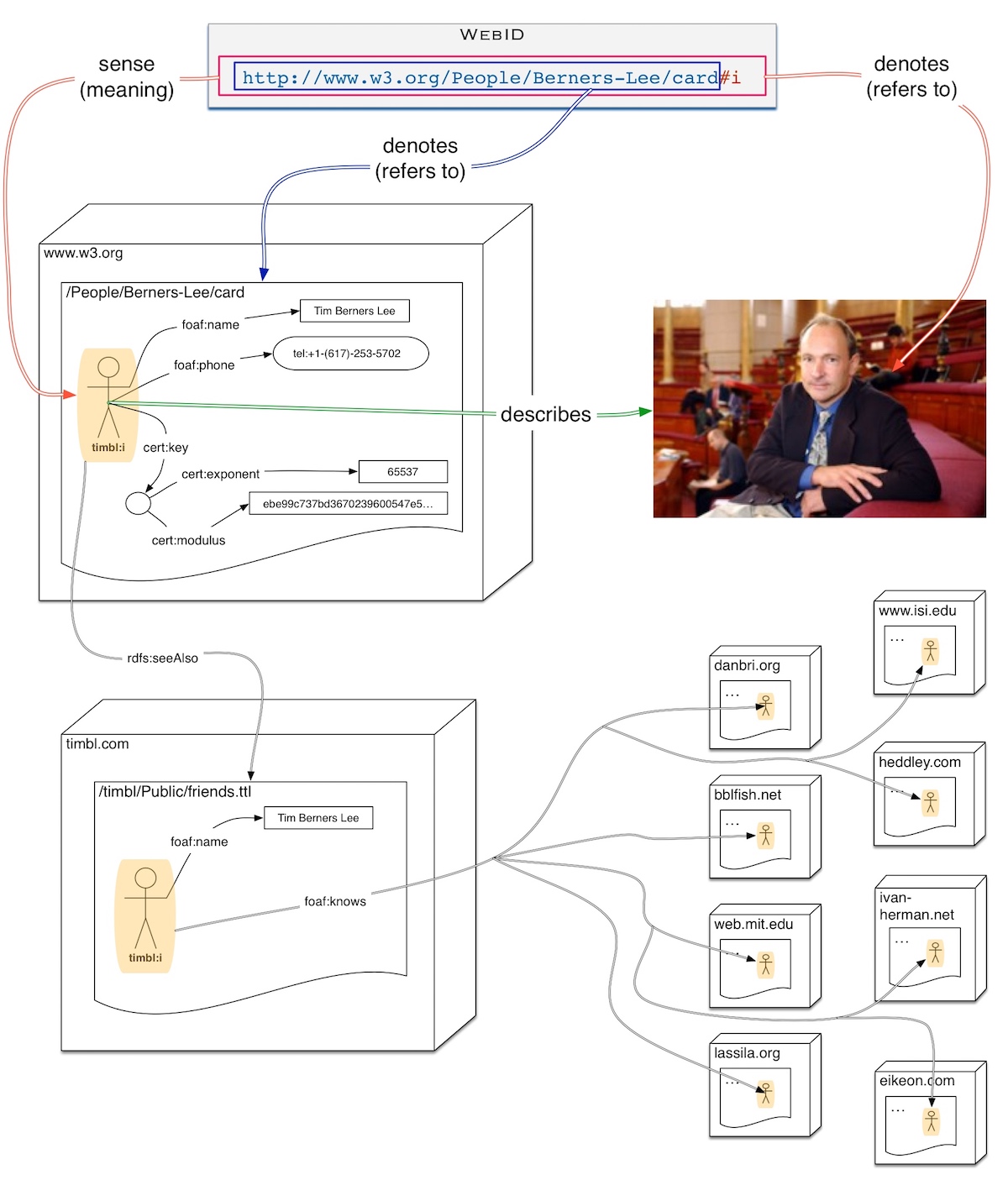

- start from a WebID which is a URL for a person - we have illustrated this in the graphic below with a URL that refers to Tim Berners Lee - whose sense is given by a PointedGraph retrieved from the rdf graph built up at the document location of the URI without the fragment,

- find specific links from there to

rdfs:seeAlsodocuments in case the WebID owner has placed more information in other documents for purposes of access control perhaps, and then point that graph on the WebID we were working with. - and from either of those try to jump via the

foaf:knowsrelation to the descriptions of those people as given by the owners of the names space of those URLs themselves, hosted on servers owned by potentially completely unrelated organisations. Tim Berners Lee has over 60 links to people on a large number of servers some of them illustrated in the graphic below

This is what web crawlers for search engines do when the follow links from one web page to another, taking html data, parsing it in order to index the words, and extract links to new pages that they can then fetch. But as links in html pages have until recently been very weakly typed, the only thing one can glean from such links automatically are that there are links between two pages and that the link has been taged in some way. RDFa deployment is of course changing the situation even here for html pages.

Once one moves to RDF one can follow links that are much more strongly typed: in our case by following rdf:seeAlso or foaf:knows links.

scala.concurrent.Future allows us to execute a function and get a handle on the future result, enabling us then to specify transformations on that result and hand any resultant future to other functions. But the result of the future will not be available until all the function it is wrapping have completed executing with the initial data they were given. This is not a problem for relatively atomic requests.

But in cases where we wish to process the results as they come in: perhaps we want our User Interface to start displaying information as it is received; or perhaps we want to allow some other process to start working with the partial information it has received to avoid flooding it with huge amounts of data to process all at once. The larger the potential amount of results can be, the more the streaming model of computation becomes beneficial. For infinitely many sequential requests, the streaming method of computation is the only one that can be used.

Every stream needs a source of information to get working. Sources are equivalent to the arguments passed to a function: without the argument we cannot get a value. We can produce a stream from any Sequences. Here we do this by creating a source of AkkaUris.

def uriSource(uris: AkkaUri*): Source[AkkaUri,NotUsed] =

Source(immutable.Seq(uris:_*).to[collection.immutable.Iterable])We can then transform that stream of inputs by applying asychronously a function to every element. Here we produce a new Source of PGWeb elements

val timbl = AkkaUri("https://www.w3.org/People/Berners-Lee/card#i")

val pg: Source[PGWeb, NotUsed] =

uriSource(timbl).mapAsync(1){uri =>

web.pointedGET(uri)

}Since we only started with a URI source of one element timbl, this is not very different just calling web.pointedGET(uri). But it does show how we can use a Future to build a minimal Stream.

Next we want to be able to transform such a source through a function that jumps from the initial pointed graphs to all the rdfs:seeAlso graphs attached to the pointer and add those to the stream. This is what the following flow does, taking an input stream of PGWebs and outputting a stream of Try[PGWeb] - since we may have failures that we would like to know about when jumping to the

def addSeeAlso: Flow[PGWeb,Try[PGWeb],_] = Flow[PGWeb].mapConcat{ pgweb =>

val seqFut: immutable.Seq[Future[PGWeb]] = pgweb.jump(rdfs.seeAlso).to[immutable.Seq]

//we want the see Also docs to be pointing to the same URI as the original pgweb

val seeAlso = seqFut.map(fut => fut.map( _.map(pg=>PointedGraph[Rdf](pgweb.content.pointer,pg.graph) )))

(seeAlso :+ Future.successful(pgweb)).map(neverFail(_))

}.via(flattenFutureFlow(50)) // 50 is a bit arbitraryThe sequence of actions is quite simple:

- for each pgweb object that enters the flow we jump to all

rdfs.seeAlsoresources, which gives us a sequence of futurePGWebobjects. - Then we transform all the

seeAlsopointed graphs returned above to point to the same object pointed to by the initial pointed graph, namelytimblin our previous examples. - finally we then add those

seeAlsopointed graphs to our original one making sure they never fail, by mapping them through thetransform(Success(_))function. - We then flatten this Seq of Futures by passing the flow to

flattenFutureFlow, which changes the order of the sequence to return whatever response arrives first.

def flattenFutureFlow[X](n: Int=1): Flow[Future[X],X,_] =

Flow[Future[X]].mapAsyncUnordered(n)(identity)So we can see this working in streaming mode by materializing the stream

val f = uriSource(timbl).mapAsync(1){uri => web.pointedGET(uri)}

.via(addSeeAlso).runForeach{ println(_) }This will print a couple of results to the console before the future is even done. We could have done something else instead of printing out, such as calling another web service.

Next we would like to follow the previous links by jumps through the foaf.knows relation to other graphs. Since people usually know more than a few people this should greatly increase the size of the streams.

def foafKnowsSource(webid: AkkaUri): Source[Try[PGWeb],_] =

uriSource(webid).mapAsync(1){uri => web.pointedGET(uri)}

.via(addSeeAlso)

.mapConcat{ //jump to remote foaf.knows

case Success(pgweb) => pgweb.jump(foaf.knows).to[immutable.Iterable].map(neverFail(_))

case failure => immutable.Iterable(Future.successful(failure))

}.via(flattenFutureFlow(50))Here we have added the .mapConcat{ ...} function to the code discussed previously, in order to jump over the foaf.knows relation and reach the friends profiles. This is illustrated by the arrows coming out of the server timbl.com in the above diagram and pointing each to various resources on a number of different servers shown on the right of the diagram.

If we want to run this and view the results as the arrives we can

foafKnowsSource(timbl).runForeach{ trypgw =>

println(trypgw.map(_.origin))

}For a full view of the returned structures we can fold the stream into a list

val m = foafKnowsSource(timbl).toMat(

Sink.fold(List[Try[PGWeb]]()

){ case (l,t)=> t::l })(Keep.right)

val r = m.runThis will return a resulting Future, which will be complete only when all the requests have been made. But it can be very useful to then look at the returned data structure to see what the failures are due to.

val data = r.value.get.get

browse(data)

Web.consciensciousFriends(timbl).toMat(

Sink.fold(List[PGWeb]()){ case (l,t)=> t::l }

)(Keep.right).runThe concepts presented here in a practical way were part of a presentation at Scala eXchange given in 2014. This presentation and this hack session go well together - indeed I used the pictures from the presentation to illustrate the code here.

- allow the user to choose whether he wishes to use Sesame, Jena or Plantain with by genericizing the code to

Rdfand allowing the user to choose whetherval Rdf = Sesameorval Rdf=Jena... - Save the code to scripts and add them to banana-rdf repo so that one can tweak them more easily - to avoid the cut and paste required above